Identification. The Republic of Indonesia, the world's fourth most populous nation, has 203 million people living on nearly one thousand permanently settled islands. Some two-to-three hundred ethnic groups with their own languages and dialects range in population from the Javanese (about 70 million) and Sundanese (about 30 million) on Java, to peoples numbering in the thousands on remote islands. The nature of Indonesian national culture is somewhat analogous to that of India—multicultural, rooted in older societies and interethnic relations, and developed in twentieth century nationalist struggles against a European imperialism that nonetheless forged that nation and many of its institutions. The national culture is most easily observed in cities but aspects of it now reach into the countryside as well. Indonesia's borders are those of the Netherlands East Indies, which was fully formed at the beginning of the twentieth century, though Dutch imperialism began early in the seventeenth century. Indonesian culture has historical roots, institutions, customs, values, and beliefs that many of its people share, but it is also a work in progress that is undergoing particular stresses at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

The name Indonesia, meaning Indian Islands, was coined by an Englishman, J. R. Logan, in Malaya in 1850. Derived from the Greek, Indos (India) and nesos (island), it has parallels in Melanesia, "black islands"; Micronesia, "small islands"; and Polynesia, "many islands." A German geographer, Adolf Bastian, used it in the title of his book, Indonesien , in 1884, and in 1928 nationalists adopted it as the name of their hoped-for nation.

Most islands are multiethnic, with large and small groups forming geographical enclaves. Towns within such enclaves include the dominant ethnic group and some members of immigrant groups. Large cities may consist of many ethnic groups; some cities have a dominant majority. Regions, such as West Sumatra or South Sulawesi, have developed over centuries through the interaction of geography (such as rivers, ports, plains, and mountains), historical interaction of peoples, and political-administrative policies. Some, such as North Sumatra, South Sulawesi, and East Java are ethnically mixed to varying degrees; others such as West Sumatra, Bali, and Aceh are more homogeneous. Some regions, such as South Sumatra, South Kalimantan, and South Sulawesi, share a long-term Malayo-Muslim coastal influence that gives them similar cultural features, from arts and dress to political and class stratification to religion. Upland or upriver peoples in these regions have different social, cultural, and religious orientations, but may feel themselves or be perforce a part of that region. Many such regions have become government provinces, as are the latter three above. Others, such as Bali, have not.

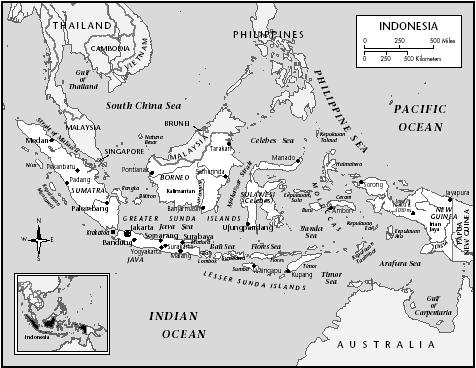

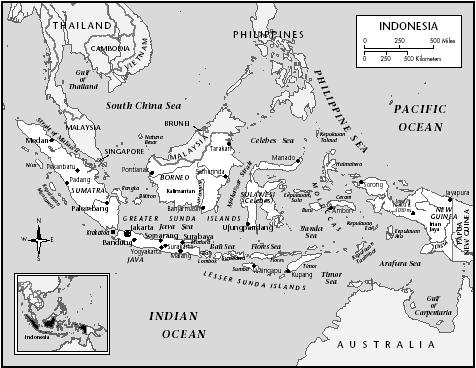

Location and Geography. Indonesia, the world's largest archipelago nation, is located astride the equator in the humid tropics and extends some 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) east-west, about the same as the contiguous United States. It is surrounded by oceans, seas, and straits except where it shares an island border with East Malaysia and Brunei on Borneo (Kalimantan); with Papua New Guinea on New Guinea; and with Timor Loro Sae on Timor. West Malaysia lies across the Straits of Malaka, the Philippines lies to the northeast, and Australia lies to the south.

The archipelago's location has played a profound role in economic, political, cultural, and religious developments there. For more than two thousand years, trading ships sailed between the great civilizations of India and China via the waters and islands of the Indies. The islands also supplied

Indonesia

spices and forest products to that trade. The alternating east and west monsoon winds made the Indies a layover point for traders and others from diverse nations who brought their languages, ideas about political order, and their arts and religions. Small and then large kingdoms grew as a result of, and as part of, that great trade. Steamships altered some trade patterns, but the region's strategic location between East and South Asia and the Middle East remains.

Indonesia consists of all or part of some of the world's largest islands—Sumatra, Java, most of Kalimantan (Borneo), Sulawesi (Celebes), Halmahera, and the west half of New Guinea (Papua)—and numerous smaller islands, of which Bali (just east of Java) is best known. These islands plus some others have mountain peaks of 9,000 feet (2,700 meters) or more, and there are some four hundred volcanos, of which one hundred are active. Between 1973 and 1990, for example, there were twenty-nine recorded eruptions, some with tragic consequences. Volcanic lava and ash contributed to the rich soils of upland Sumatra and all of Java and Bali, which have nurtured rice cultivation for several thousand years.

The inner islands of Java, Madura, and Bali make up the geographical and population center of the archipelago. Java, one of the world's most densely settled places (with 2,108 people per square mile [814 per square kilometer] in 1990), occupies 78 percent of the nation's land area but accounts for about 60 percent of Indonesia's population. (About the size of New York state, Java's population is equivalent to 40 percent of that of the United States.) The outer islands, which form an arc west, north, and east of the inner ones, have about 90 percent of the land area of the country but only about 42 percent of the population. The cultures of the inner islands are more homogeneous, with only four major cultural groups: the Sundanese (in West Java), the Javanese (in Central and East Java), the Madurese (on Madura and in East Java), and the Balinese (on Bali). The outer islands have hundreds of ethnolinguistic groups.

Forests of the inner islands, once plentiful, are now largely gone. Kalimantan, West Papua, and Sumatra still have rich jungles, though these are threatened by population expansion and exploitation by loggers for domestic timber use and export. Land beneath the jungles is not fertile. Some eastern islands, such as Sulawesi and the Lesser Sundas (the island chain east of Bali), also have lost forests.

Two types of agriculture are predominant in Indonesia: permanent irrigated rice farming ( sawah ) and rotating swidden or slash-and-burn ( ladang ) farming of rice, corn, and other crops. The former dominates Java, Bali, and the highlands all along the western coast of Sumatra; the latter is found in other parts of Sumatra and other outer islands, but not exclusively so. Fixed rain-fed fields of rice are prominent in Sulawesi and some other places. Many areas are rich in vegetables, tropical fruit, sago, and other cultivated or forest crops, and commercial plantations of coffee, tea, tobacco, coconuts, and sugar are found in both inner and outer islands. Plantation-grown products such as rubber, palm oil, and sisal are prominent in Sumatra, while coffee, sugar, and tea are prominent in Java. Spices such as cloves, nutmeg, and pepper are grown mainly in the outer islands, especially to the east. Maluku (formerly the Moluccas) gained its appellation the "Spice Islands" from the importance of trade in these items. Gold, tin, and nickel are mined in Sumatra, Bangka, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua for domestic and international markets, and oil and liquified natural gas (especially from Sumatra) are important exports. Numerous rivers flowing from mountainous or jungle interiors to coastal plains and ports have carried farm and forest products for centuries and have been channels for cultural communication.

Demography. Indonesia's population increased from 119,208,000 in 1971 to 147,500,000 in 1980, to 179,300,000 in 1990, and to 203,456,000 in 2000. In the meantime the fertility rate declined from 4.6 per thousand women to 3.3; the crude death rate fell at a rate of 2.3 percent per year; and infant mortality declined from 90.3 per thousand live births to 58. The fertility rate was projected to fall to 2.1 percent within another decade, but the total population was predicted to reach 253,700,000 by 2020. As of the middle of the twentieth century, Indonesia's population was largely rural, but at the beginning of the twenty-first century, about 20 percent live in towns and cities and three of five people farm.

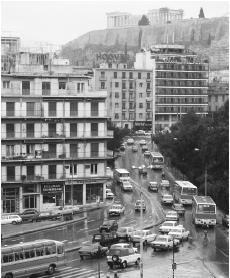

Cities in both inner and outer islands have grown rapidly, and there are now twenty-six cities with populations over 200,000. As in many developing countries, Indonesia's population is still a young one. The above patterns are national, but there are ethnic and regional variations. Population has grown at different rates in different areas owing to such factors as economic conditions and standard of living, nutrition, availability and effectiveness of public health and family planning programs, and cultural values and practices.

Migration also plays a part in population fluctuations. Increased permanent or seasonal migration to cities accompanied economic development during the 1980s and 1990s, but there is also significant migration between rural areas as people leave places such as South Sulawesi for more productive work or farm opportunities in Central Sumatra or East Kalimantan.

Linguistic Affiliation. Nearly all of Indonesia's three hundred to four hundred languages are subgroups of the Austronesian family that extends from Malaysia through the Philippines, north to several hill peoples of Vietnam and Taiwan, and to Polynesia, including Hawaiian and Maori (of New Zealand) peoples. Indonesia's languages are not mutually intelligible, though some subgroups are more similar than others (as Europe's Romance languages are closer to each other than to Germanic ones, though both are of the Indo-European family). Some language subgroups have sub-subgroups, also not mutually intelligible, and many have local dialects. Two languages—one in north Halmahera, one in West Timor—are non-Austronesian and, like Basque in Europe, are not related to other known languages. Also, the very numerous languages of Papua are non-Austronesian.

Most people's first language is a local one. In 1923, however, the Malay language (now known as Bahasa Malaysia in Malaysia where it is the official language) was adopted as the national language at a congress of Indonesian nationalists, though only a small minority living in Sumatra along the Straits of Malaka spoke it as their native language. Nevertheless, it made sense for two reasons.

First, Malay had long been a commercial and governmental lingua franca that bound diverse peoples. Ethnically diverse traders and local peoples used Malay in ports and hinterlands in its grammatically simplified form known as "market Malay." Colonial

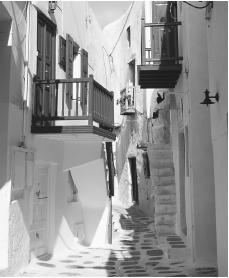

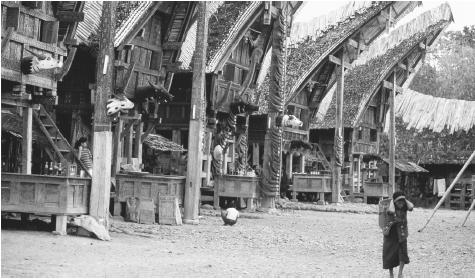

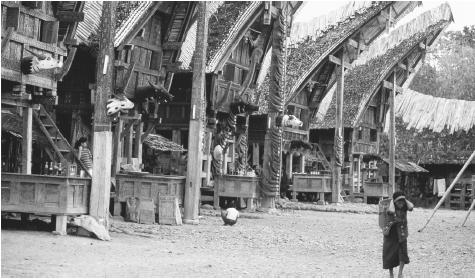

A row of tongkona houses in the Toraja village of Palawa. The buffalo horns tied to the poles supporting the massive gable of these houses are a sign of wealth and reputation.

governments in British Malaya and the Netherlands Indies used high Malay in official documents and negotiations and Christian missionaries first translated the Bible into that language.

Second, nationalists from various parts of the archipelago saw the value of a national language not associated with the largest group, the Javanese. Bahasa Indonesia is now the language of government, schools, courts, print and electronic media, literary arts and movies, and interethnic communication. It is increasingly important for young people, and has a youth slang. In homes, a native language of the family is often spoken, with Indonesian used outside the home in multiethnic areas. (In more monolingual areas of Java, Javanese also serves outside the home.) Native languages are not used for instruction beyond the third grade in some rural areas. Native language literatures are no longer found as they were in colonial times. Many people lament the weakening of native languages, which are rich links to indigenous cultures, and fear their loss to modernization, but little is done to maintain them. The old and small generation of well-educated Indonesians who spoke Dutch is passing away. Dutch is not known by most young and middle-aged people, including students and teachers of history who cannot read much of the documentary history of the archipelago. English is the official second language taught in schools and universities with varying degrees of success.

Symbolism. The national motto, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika , is an old Javanese expression usually translated as "unity in diversity." The nation's official ideology, first formulated by President Sukarno in 1945, is the Pancasila, or Five Principles: belief in one supreme God; just and civilized humanitarianism; Indonesian unity; popular sovereignty governed by wise policies arrived at through deliberation and representation; and social justice for all Indonesian people. Indonesia was defined from the beginning as the inheritor of the Netherlands East Indies. Though West Papua remained under the Dutch until 1962, Indonesia conducted a successful international campaign to secure it. Indonesia's occupation of the former Portuguese East Timor in 1975, never recognized by the United Nations, conflicted with this founding notion of the nation. After two decades of bitter struggle there, Indonesia withdrew.

Since 1950 the national anthem and other songs have been sung by children throughout the country to begin the school day; by civil servants at flag-raising ceremonies; over the radio to begin and close broadcasting; in cinemas and on television; and at national day celebrations. Radio and television, government owned and controlled for much of the second half of the twentieth century, produced nationalizing programs as diverse as Indonesian language lessons, regional and ethnic dances and songs, and plays on national themes. Officially recognized "national heroes" from diverse regions are honored in school texts, and biographies and with statues for their struggles against the Dutch; some regions monumentalize local heros of their own.

HISTORY AND ETHNIC RELATIONS

Emergence of the Nation. Though the Republic of Indonesia is only fifty years old, Indonesian societies have a long history during which local and wider cultures were formed.

About 200 C.E. , small states that were deeply influenced by Indian civilization began to develop in Southeast Asia, primarily at estuaries of major rivers. The next five hundred to one thousand years saw great states arise with magnificent architecture. Hinduism and Buddhism, writing systems, notions of divine kingship, and legal systems from India were adapted to local scenes. Sanskrit terms entered many of the languages of Indonesia. Hinduism influenced cultures throughout Southeast Asia, but only one people are Hindu, the Balinese.

Indianized states declined about 1400 C.E. with the arrival of Muslim traders and teachers from India, Yemen, and Persia, and then Europeans from Portugal, Spain, Holland, and Britain. All came to join the great trade with India and China. Over the next two centuries local princedoms traded, allied, and fought with Europeans, and the Dutch East India Company became a small state engaging in local battles and alliances to secure trade. The Dutch East India Company was powerful until 1799 when the company went bankrupt. In the nineteenth century the Dutch formed the Netherlands Indies government, which developed alliances with rulers in the archipelago. Only at the beginning of the twentieth century did the Netherlands Indies government extend its authority by military means to all of present Indonesia.

Sporadic nineteenth century revolts against Dutch practices occurred mainly in Java, but it was in the early twentieth century that Indonesian intellectual and religious leaders began to seek national independence. In 1942 the Japanese occupied the Indies, defeating the colonial army and imprisoning the Dutch under harsh conditions.

On 17 August 1945, following Japan's defeat in World War II, Indonesian nationalists led by Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared Indonesian independence. The Dutch did not accept and for five years fought the new republic, mainly in Java. Indonesian independence was established in 1950.

National Identity. Indonesia's size and ethnic diversity has made national identity problematic and debated. Identity is defined at many levels: by Indonesian citizenship; by recognition of the flag, national anthem, and certain other songs; by recognition of national holidays; and by education about Indonesia's history and the Five Principles on which the nation is based. Much of this is instilled through the schools and the media, both of which have been closely regulated by the government during most of the years of independence. The nation's history has been focused upon resistance to colonialism and communism by national heroes and leaders who are enshrined in street names. Glories of past civilizations are recognized, though archaeological remains are mainly of Javanese principalities.

Ethnic Relations. Ethnic relations in the archipelago have long been a concern. Indonesian leaders recognized the possibility of ethnic and regional separatism from the beginning of the republic. War was waged by the central government against separatism in Aceh, other parts of Sumatra, and Sulawesi in the 1950s and early 1960s, and the nation was held together by military force.

The relationships between native Indonesians and overseas Chinese have been greatly influenced by Dutch and Indonesian government policies. The Chinese number about four to six million, or 3 percent of the population, but are said to control as much as 60 percent of the nation's wealth. The Chinese traded and resided in the islands for centuries, but in the nineteenth century the Dutch brought in many more of them to work on plantations or in mines. The Dutch also established a social, economic, and legal stratification system that separated Europeans, foreign Asiatics and Indo-Europeans, and Native Indonesians, partly to protect native Indonesians so that their land could not be lost to outsiders. The Chinese had little incentive to assimilate to local societies, which in turn had no interest in accepting them.

Even naturalized Chinese citizens faced restrictive regulations, despite cozy business relationships between Chinese leaders and Indonesian officers and bureaucrats. Periodic violence directed toward Chinese persons and property also occurred. In the colonial social system, mixed marriages between Chinese men and indigenous women produced half-castes ( peranakan ), who had their own organizations, dress, and art forms, and even newspapers. The same was true for people of mixed Indonesian-European descent (called Indos, for short).

Ethnolinguistic groups reside mainly in defined areas where most people share much of the same culture and language, especially in rural areas. Exceptions are found along borders between groups, in places where other groups have moved in voluntarily or as part of transmigration programs, and in cities. Such areas are few in Java, for example, but more common in parts of Sumatra.

Religious and ethnic differences may be related. Indonesia has the largest Muslim population of any country in the world, and many ethnic groups are exclusively Muslim. Dutch policy allowed proselytization by Protestants and Catholics among separate groups who followed traditional religions; thus today many ethnic groups are exclusively Protestant or Roman Catholic. They are heavily represented among upriver or upland peoples in North Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, and the eastern Lesser Sundas, though many Christians are also found in Java and among the Chinese. Tensions arise when groups of one religion migrate to a place with a different established religion. Political and economic power becomes linked to both ethnicity and religion as groups favor their own kinsmen and ethnic mates for jobs and other benefits.

URBANISM , ARCHITECTURE, AND THE USE OF SPACE

Javanese princes long used monuments and architecture to magnify their glory, provide a physical focus for their earthly kingdoms, and link themselves to the supernatural. In the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries the Dutch reinforced the position of indigenous princes through whom they ruled by building them stately palaces. Palace architecture over time combined Hindu, Muslim, indigenous, and European elements and symbols in varying degrees depending upon the local situation, which can still be seen in palaces at Yogyakarta and Surakarta in Java or in Medan, North Sumatra.

Dutch colonial architecture combined Roman imperial elements with adaptations to tropical weather and indigenous architecture. The Dutch fort and early buildings of Jakarta have been restored. Under President Sukarno a series of statues were built around Jakarta, mainly glorifying the people; later, the National Monument, the Liberation of West Irian (Papua) Monument, and the great Istiqlal Mosque were erected to express the link to a Hindu past, the culmination of Indonesia's independence, and the place of Islam in the nation. Statues to national heroes are found in regional cities.

Residential architecture for different urban socioeconomic groups was built on models developed by the colonial government and used throughout the Indies. It combined Dutch elements (highpitched tile roofs) with porches, open kitchens, and servants quarters suited to the climate and social system. Wood predominated in early urban architecture, but stone became dominant by the twentieth century. Older residential areas in Jakarta, such as Menteng near Hotel Indonesia, reflect urban architecture that developed in the 1920s and 1930s. After 1950, new residential areas continued to develop to the south of the city, many with elaborate homes and shopping centers.

The majority of people in many cities live in small stone and wood or bamboo homes in crowded urban villages or compounds with poor access to clean water and adequate waste disposal. Houses are often tightly squeezed together, particularly in Java's large cities. Cities that have less pressure from rural migrants, such as Padang in West Sumatra and Manado in North Sulawesi, have been able to better manage their growth.

Traditional houses, which are built in a single style according to customary canons of particular ethnic groups, have been markers of ethnicity. Such houses exist in varying degrees of purity in rural areas, and some aspects of them are used in such urban architecture as government buildings, banks, markets and homes.

Traditional houses in many rural villages are declining in numbers. The Dutch and Indonesian governments encouraged people to build "modern" houses, rectangular structures with windows. In some rural areas, however, such as West Sumatra, restored or new traditional houses are built by successful urban migrants to display their success. In other rural areas people display status by building modern houses of stone and tile, with precious glass windows. In the cities, old colonial homes are renovated by prosperous owners who put newer contemporary-style fronts on the houses. The roman columns favored in Dutch public buildings are now popular for private homes.

FOOD AND ECONOMY

Food in Daily Life. Indonesian cuisine reflects regional, ethnic, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Indian, and Western influences, and daily food quality, quantity,

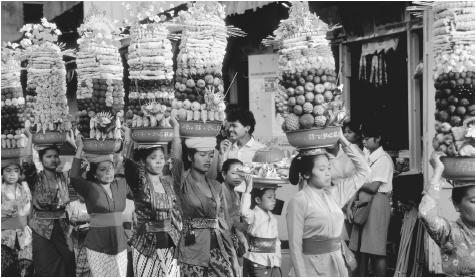

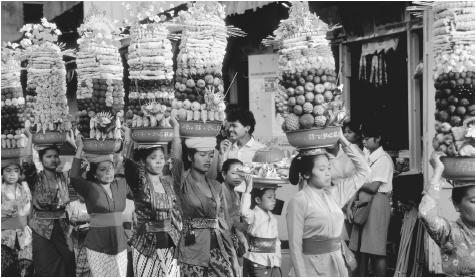

Women carry towering baskets of fruit on their heads for a temple festival in Bali.

and diversity vary greatly by socioeconomic class, season, and ecological conditions. Rice is a staple element in most regional cooking and the center of general Indonesian cuisine. (Government employees receive monthly rice rations in addition to salaries.) Side dishes of meat, fish, eggs, and vegetables and a variety of condiments and sauces using chili peppers and other spices accompany rice. The cuisine of Java and Bali has the greatest variety, while that of the Batak has much less, even in affluent homes, and is marked by more rice and fewer side dishes. And rice is not the staple everywhere: in Maluku and parts of Sulawesi it is sago, and in West Timor it is maize (corn), with rice consumed only for ceremonial occasions. Among the Rotinese, palm sugar is fundamental to the diet.

Indonesia is an island nation, but fish plays a relatively small part in the diets of the many people who live in the mountainous interiors, though improved transportation makes more salted fish available to them. Refrigeration is still rare, daily markets predominate, and the availability of food may depend primarily upon local produce. Indonesia is rich in tropical fruit, but many areas have few fruit trees and little capacity for timely transportation of fruit. Cities provide the greatest variety of food and types of markets, including modern supermarkets; rural areas much less so. In cities, prosperous people have access to great variety while the poor have very limited diets, with rice predominant and meat uncommon. Some poor rural regions experience what people call "ordinary hunger" each year before the corn and rice harvest.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. The most striking ceremonial occasion is the Muslim month of fasting, Ramadan. Even less-observant Muslims fast seriously from sunup to sundown despite the tropical heat. Each night during Ramadan, fine celebratory meals are held. The month ends with Idul Fitri, a national holiday when family, friends, neighbors, and work associates visit each other's homes to share food treats (including visits by non-Muslims to Muslim homes).

In traditional ritual, special food is served to the spirits or the deceased and eaten by the participants. The ubiquitous Javanese ritual, selamatan , is marked by a meal between the celebrants and is held at all sorts of events, from life-cycle rituals to the blessing of new things entering a village. Life-cycle events, particularly marriages and funerals, are the main occasions for ceremonies in both rural and urban areas, and each has religious and secular aspects. Elaborate food service and symbolism are features of such events, but the content varies greatly in different ethnic groups. Among the Meto of Timor, for example, such events must have meat and rice ( sisi-maka' ), with men cooking the former and women the latter. Elaborate funerals involve drinking a mixture of pork fat and blood that is not part of the daily diet and that may be unappetizing to many participants who nonetheless follow tradition. At such events, Muslim guests are fed at separate kitchens and tables.

In most parts of Indonesia the ability to serve an elaborate meal to many guests is a mark of hospitality, capability, resources, and status of family or clan whether for a highland Toraja buffalo sacrifice at a funeral or for a Javanese marriage reception in a five-star hotel in Jakarta. Among some peoples, such as the Batak and Toraja, portions of animals slaughtered for such events are important gifts for those who attend, and the part of the animal that is selected symbolically marks the status of the recipient.

Basic Economy. About 60 percent of the population are farmers who produce subsistence and market-oriented crops such as rice, vegetables, fruit, tea, coffee, sugar, and spices. Large plantations are devoted to oil palm, rubber, sugar, and sisel for domestic use and export, though in some areas rubber trees are owned and tapped by farmers. Common farm animals are cattle, water buffalo, horses, chickens, and, in non-Muslim areas, pigs. Both freshwater and ocean fishing are important to village and national economies. Timber and processed wood, especially in Kalimantan and Sumatra, are important for both domestic consumption and export, while oil, natural gas, tin, copper, aluminum, and gold are exploited mainly for export. In colonial times, Indonesia was characterized as having a "dual economy." One part was oriented to agriculture and small crafts for domestic consumption and was largely conducted by native Indonesians; the other part was export-oriented plantation agriculture and mining (and the service industries supporting them), and was dominated by the Dutch and other Europeans and by the Chinese. Though Indonesians are now important in both aspects of the economy and the Dutch/European role is no longer so direct, many features of that dual economy remain, and along with it are continuing ethnic and social dissatisfactions that arise from it.

One important aspect of change during Suharto's "New Order" regime (1968–1998) was the rapid urbanization and industrial production on Java, where the production of goods for domestic use and export expanded greatly. The previous imbalance in production between Java and the Outer Islands is changing, and the island now plays an economic role in the nation more in proportion to its population. Though economic development between 1968 and 1997 aided most people, the disparity between rich and poor and between urban and rural areas widened, again particularly on Java. The severe economic downturn in the nation and the region after 1997, and the political instability with the fall of Suharto, drastically reduced foreign investment in Indonesia, and the lower and middle classes, particularly in the cities, suffered most from this recession.

Land Tenure and Property. The colonial government recognized traditional rights of indigenous peoples to land and property and established semicodified "customary law" to this end. In many areas of Indonesia longstanding rights to land are held by groups such as clans, communities, or kin groups. Individuals and families use but do not own land. Boundaries of communally held land may be fluid, and conflicts over usage are usually settled by village authorities, though some disputes may reach government officials or courts. In cities and some rural areas of Java, European law of ownership was established. Since Indonesian independence various sorts of "land reform" have been called for and have met political resistance. During Suharto's regime, powerful economic and political groups and individuals obtained land by quasi-legal means and through some force in the name of "development," but serving their monied interest in land for timber, agro-business, and animal husbandry; business locations, hotels, and resorts; and residential and factory expansion. Such land was often obtained with minimal compensation to previous owners or occupants who had little legal recourse. The same was done by government and public corporations for large-scale projects such as dams and reservoirs, industrial parks, and highways. Particularly vulnerable were remote peoples (and animals) in forested areas where timber export concessions were granted to powerful individuals.

Commercial Activities. For centuries, commerce has been conducted between the many islands and beyond the present national borders by traders for various local and foreign ethnic groups. Some indigenous peoples such as the Minangkabau, Bugis, and Makassarese are well-known traders, as are the Chinese. Bugis sailing ships, which are built entirely by hand and range in size from 30 to 150 tons (27 to 136 metric tons), still carry goods to many parts of the nation. Trade between lowlands and highlands and coasts and inland areas is handled by these and other small traders in complex market systems

Women carrying firewood in Flores. In Indonesia, men and women share many aspects of village agriculture.

involving hundreds of thousands of men and women traders and various forms of transport, from human shoulders, horses, carts, and bicycles, to minivans, trucks, buses, and boats. Islam spread along such market networks, and Muslim traders are prominent in small-scale trade everywhere.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the Dutch used the Chinese to link rural farms and plantations of native Indonesians to small-town markets and these to larger towns and cities where the Chinese and Dutch controlled large commercial establishments, banks, and transportation. Thus Chinese Indonesians became a major force in the economy, controlling today an estimated 60 percent of the nation's wealth though constituting only about 4 percent of its population. Since independence, this has led to suppression of Chinese ethnicity, language, education, and ceremonies by the government and to second-class citizenship for those who choose to become Indonesian nationals. Periodic outbreaks of violence against the Chinese have occurred, particularly in Java. Muslim small traders, who felt alienated in colonial times and welcomed a change with independence, have been frustrated as New Order Indonesian business, governmental, and military elites forged alliances with the Chinese in the name of "development" and to their financial benefit.

Major Industries. Indonesia's major industries involve agro-business, resource extraction and export, construction, and tourism, but a small to medium-sized industrial sector has developed since the 1970s, especially in Java. It serves domestic demand for goods (from household glassware and toothbrushes to automobiles), and produces a wide range of licensed items for multinational companies. Agro-business and resource extraction, which still supply Indonesia with much of its foreign exchange and domestic operating funds, are primarily in the outer islands, especially Sumatra (plantations, oil, gas, and mines), Kalimantan (timber), and West Papua (mining). The industrial sector has grown in Java, particularly around Jakarta and Surabaya and some smaller cities on the north coast.

S OCIAL S TRATIFICATION

Classes and Castes. Aristocratic states and hierarchically-ordered chiefdoms were features of many Indonesian societies for the past millennium. Societies without such political systems existed, though most had the principle of hierarchy. Hindu states that later turned to Islam had aristocracies at the top and peasants and slaves at the bottom of society. Princes in their capitals concentrated secular and spiritual power and conducted rites for their principalities, and they warred for subjects, booty and land, and control of the sea trade. The Dutch East India Company became a warring state with its own forts, military, and navy, and it allied with and fought indigenous states. The Netherlands Indies government succeeded the company, and the Dutch ruled some areas directly and other areas indirectly via native princes. In some areas they augmented the power of indigenous princes and widened the gap between aristocrats and peasants. In Java, the Dutch augmented the pomp of princes while limiting their authority responsibility; and in other areas, such as East Sumatra, the Dutch created principalities and princely lines for their own economic and political benefit.

In general, princes ruled over areas of their own ethnic group, though some areas were multiethnic in character, particularly larger ones in Java or the port principalities in Sumatra and Kalimantan. In the latter, Malay princes ruled over areas consisting of a variety of ethnic groups. Stratified kingdoms and chiefdoms were entrenched in much of Java, the Western Lesser Sundas and parts of the Eastern Lesser Sundas, South Sulawesi, parts of Maluku, parts of Kalimantan, and the east and southeast coast of Sumatra.

Members of ruling classes gained wealth and the children of native rulers were educated in schools that brought them in contact with their peers from other parts of the archipelago.

Not all Indonesian societies were as socially stratified as that of Java. Minangkabau society was influenced by royal political patterns, but evolved into a more egalitarian political system in its West Sumatran homeland. The Batak of North Sumatra developed an egalitarian political order and ethos combining fierce clan loyalty with individuality. Upland or upriver peoples in Sulawesi and Kalimantan also developed more egalitarian social orders, though they could be linked to the outside world through tribute to coastal princes.

Symbols of Social Stratification. The aristocratic cultures of Java and the Malay-influenced coastal principalities were marked by ceremonial isolation of the princes and aristocrats, tribute by peasants and lesser lords, deference to authority by peasants, sumptuary rules marking off classes, the maintenance by aristocrats of supernaturally powerful regalia, and high court artistic and literary cultures. The Dutch in turn surrounded themselves with some of the same aura and social rules in their interaction with native peoples, especially during the late colonial period when European women came to the Indies and Dutch families were founded. In Java in particular, classes were separated by the use of different language levels, titles, and marriage rules. Aristocratic court culture became a paragon of refined social behavior in contrast to the rough or crude behavior of the peasants or non-Javanese. Indirection in communication and self-control in public behavior became hallmarks of the refined person, notions that spread widely in society. The courts were also exemplary centers for the arts— music, dance, theater, puppetry, poetry, and crafts such as batik cloth and silverworking. The major courts became Muslim by the seventeenth century, but some older Hindu philosophical and artistic practices continued to exist there or were blended with Muslim teachings.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a more complex society developed in Java and some other parts of the Indies, which created a greater demand for trained people in government and commerce than the aristocratic classes could provide, and education was somewhat more widely provided. A class of urbanized government officials and professionals developed that often imitated styles of the earlier aristocracy. Within two decades after independence, all principalities except the sultanates of Yogyakarta and Surakarta were eliminated throughout the republic. Nevertheless, behaviors and thought patterns instilled through generations of indigenous princely rule—deference to authority, paternalism, unaccountability of leaders, supernaturalistic power, ostentatious displays of wealth, rule by individuals and by force rather than by law—continue to exert their influence in Indonesian society.

POLITICAL LFE

Government. During 2000, Indonesia was in deep governmental crisis and various institutions were being redesigned. The 1945 constitution of the republic, however, mandates six organs of the state: the People's Consultative Assembly ( Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat , or MPR), the presidency, the People's Representative Council ( Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat , or DPR), the Supreme Advisory Council ( Dewan Pertimbangan Agung ), the State Audit Board ( Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan ), and the Supreme Court ( Mahkamah Agung ).

The president is elected by the MPR, which consists of one thousand members from various walks of life—farmers to businesspeople, students to soldiers—who meet once every five years to elect the president and endorse his or her coming five-year plan. The vice president is selected by the president.

The DPR meets at least once a year and has five hundred members: four hundred are elected from the provinces, one hundred are selected by the military. The DPR legislates, but its statutes must be approved by the president. The Supreme Court can hear cases from some three hundred subordinate courts in the provinces but cannot impeach or rule on the constitutionality of acts by other branches of government.

In 1997, the nation had twenty-seven provinces plus three special territories (Aceh, Yogyakarta, and Jakarta) with different forms of autonomy and their own governors. East Timor ceased to be a province in 1998, and several others are seeking provincial status. Governors of provinces are appointed by the Interior Ministry and responsible to it. Below the twenty-seven provinces are 243 districts ( kabupaten ) subdivided into 3,841 subdistricts ( kecamatan ), whose leaders are appointed by the government. There are also fifty-five municipalities, sixteen administrative municipalities, and thirty-five administrative cities with administrations separate from the provinces of which they are a part. At the base of government are some sixty-five thousand urban and rural villages called either kelurahan or desa . (Leaders of the former are appointed by the subdistrict head; the latter are elected by the people.) Many officials appointed at all levels during the New Order were military (or former military) men. Provincial, district, and subdistrict governments oversee a variety of services; the functional offices of the government bureaucracy (such as agriculture, forestry, or public works), however, extend to the district level as well and answer directly to their ministries in Jakarta, which complicates local policy making.

Leadership and Political Officials. During the New Order, the Golkar political party exerted full control over ministerial appointments and was powerfully influential in the civil service whose members were its loyalists. Funds were channeled locally to aid Golkar candidates, and they dominated the national and regional representative bodies in most parts of the country. The Muslim United Development Party and the Indonesian Democratic Party lacked such funds and influence and their leaders were weak and often divided. Ordinary people owed little to, and received little from, these parties. After the fall of President Suharto and the opening of the political system to many parties, many people became involved in politics; politics, however, mainly involves the leaders of the major

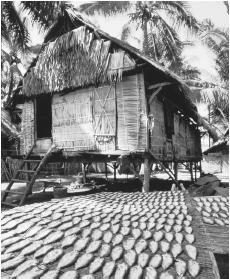

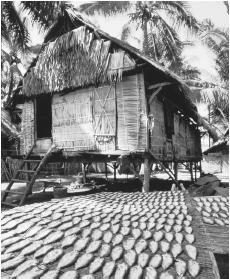

Fish drying. Both freshwater and ocean fishing are important to village economies.

parties jockeying for alliances and influence within the representative bodies at the national and provincial levels, as well as within the president's cabinet.

The civil and military services, dominant institutions since the republic's founding, are built upon colonial institutions and practices. The New Order regime increased central government authority by appointing heads of subdistricts and even villages. Government service brings a salary, security, and a pension (however modest it may be) and is highly prized. The employees at a certain level in major institutions as diverse as government ministries, public corporations, schools and universities, museums, hospitals, and cooperatives are civil servants, and such positions in the civil service are prized. Membership carried great prestige in the past, but that prestige diminished somewhat during the New Order. Economic expansion made private sector positions—especially for trained professionals— more available, more interesting, and much more lucrative. Neither the number of civil service positions nor salaries have grown comparably.

The interaction of ordinary people with government officials involves deference (and often payments) upward and paternalism downward. Officials, most of whom are poorly paid, control access to things as lucrative as a large construction contract or as modest as a permit to reside in a neighborhood, all of which can cost the suppliant special fees. International surveys have rated Indonesia among the most corrupt nations in the world. Much of it involves sharing the wealth between private persons and officials, and Indonesians note that bribes have become institutionalized. Both the police and the judiciary are weak and subject to the same pressures. The unbridled manipulation of contracts and monopolies by Suharto family members was a major precipitant of unrest among students and others that brought about the president's fall.

Social Problems and Control. At the end of the colonial period, the secular legal system was divided between native (mainly for areas governed indirectly through princes) and government (for areas governed directly through administrators). The several constitutions of the republic between 1945 and 1950 validated colonial law that did not conflict with the constitution, and established three levels of courts: state courts, high courts (for appeal), and the supreme court. Customary law is still recognized, but native princes who were once responsible for its management no longer exist and its position in state courts is uncertain.

Indonesians inherited from the Dutch the notion of "a state based upon law" ( rechtsstaat in Dutch, negara hukum in Indonesian), but implementation has been problematic and ideology triumphed over law in the first decade of independence. Pressure for economic development and personal gain during the New Order led to a court system blatantly subverted by money and influence. Many people became disenchanted with the legal system, though some lawyers led the fight against corruption and for human rights, including the rights of those affected by various development projects. A national human rights commission was formed to investigate violations in East Timor and elsewhere, but has so far had relatively little impact.

One sees the same disaffection from the police, which were a branch of the military until the end of the New Order. Great emphasis was placed upon public order during the New Order, and military and police organs were used to maintain a climate of caution and fear among not just lawbreakers but also among ordinary citizens, journalists, dissidents, labor advocates, and others who were viewed as subversive. Extrajudicial killings of alleged criminals and others were sponsored by the military in some urban and rural areas, and killings of rights activists, particularly in Atjeh, continue. The media, now free after severe New Order controls, is able to report daily on such events. In 1999– 2000, vigilante attacks against even suspected lawbreakers were becoming common in cities and some rural areas, as was an increase in violent crime. Compounding the climate of national disorder were violence among refugees in West Timor, sectarian killing between Muslims and Christians in Sulawesi and Maluku, and separatist violence in Atjeh and Papua; in all of which, elements of the police and military are seen to be participating, even fomenting, rather than controlling.

In villages many problems are never reported to the police but are still settled by local custom and mutual agreement mediated by recognized leaders. Customary settlement is frequently the only means used, but it also may be used as a first resort before appeal to courts or as a last resort by dissatisfied litigants from state courts. In multiethnic areas, disputes between members of different ethnic groups may be settled by leaders of either or both groups, by a court, or by feud. In many regions with settled populations, a customary settlement is honored over a court one, and many rural areas are peaceful havens. Local custom is often based upon restorative justice, and jailing miscreants may be considered unjust since it removes them from oversight and control of their kinsmen and neighbors and from working to compensate aggrieved or victimized persons. Where there is great population mobility, especially in cities, this form of social control is far less viable and, since the legal system is ineffective, vigilantism becomes more common.

Military Activity. The Armed Forces of the Republic of Indonesia ( Angkatan Bersenjata Republik Indonesia , or ABRI) consist of the army (about 214,000 personnel), navy (about 40,000), air force (nearly 20,000), and, until recently, state police (almost 171,000). In addition, almost three million civilians were trained in civil defense groups, student units, and other security units. The premier force, the army, was founded and commanded by members of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army and/or the Japanese-sponsored Motherland Defenders. Many soldiers at first came from the latter, but many volunteers were added after the Japanese left. Some local militias were led by people with little military experience, but their success in the war of independence made them at least local heroes. The army underwent vicissitudes after independence as former colonial officers led in transforming guerilla-bands and provincial forces into a centralized modern army, with national command structure, education, and training.

From its beginning the armed forces recognized a dual function as a defense and security force and as a social and political one, with a territorial structure (distinct from combat commands) that paralleled the civilian government from province level to district, subdistrict, and even village. General Suharto came to power as the leader of an anticommunist and nationalist army, and he made the military the major force behind the New Order. Its security and social and political functions have included monitoring social and political developments at national and local levels; providing personnel for important government departments and state enterprises; censoring the media and monitoring dissidents; placing personnel in villages to learn about local concerns and to help in development; and filling assigned blocs in representative bodies. The military owns or controls hundreds of businesses and state enterprises that provide about three-quarters of its budget, hence the difficulty for a civilian president who wishes to exert control over it. Also, powerful military and civilian officials provide protection and patronage for Chinese business-people in exchange for shares in profits and political funding.

SOCIAL WELFARE AND CHANGE PROGRAMS

The responsibility for most formal public health and social welfare programs rests primarily with government and only secondarily with private and religious organizations. From 1970 to 1990, considerable investment was made in roads and in health stations in rural and urban areas, but basic infrastructure is still lacking in many areas. Sewage and waste disposal are still poor in many urban areas, and pollution affects canals and rivers, especially in newly industrializing areas such as West Java. Welfare programs to benefit the poor are minimal compared to the need, and rural economic development activities are modest compared to those in cities. The largest and most successful effort, the national family planning program, used both government and private institutions to considerably reduce the rate of population increase in Java and other areas. Transmigration, the organized movement of people from rural Java to less populated outer island areas in Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and West Papua, was begun by the Dutch early in the twentieth century and is continued vigorously by the Indonesian government. It has led to the agricultural development of many outer island areas but has little eased population pressure in Java, and it has led to ecological problems and to ethnic and social conflicts between transmigrants and local people.

NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

Despite government dominance in many areas of social action, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have a rich history, though they often have had limited funds, have operated under government restraint, and have been limited in much of their activity to urban areas. They have served in fields such as religion, family planning, education, rural health and mutual aid, legal aid, workers' rights, philanthropy, regional or ethnic interests, literature and the arts, and ecology and conservation Muslim and Christian organizations have been active in community education and health care since the early twentieth century. Foreign religious, philanthropic, and national and international organizations have supported welfare efforts by government and NGOs, though most NGOs are homegrown. The authoritarian nature of the New Order led to tensions between the government and NGOs in areas such as legal aid, workers' rights, and conservation, and the government sought to co-opt some such organizations. Also, foreign support for NGOs led to tensions between the various governments, even cancellations of aid, when that support was viewed as politically motivated. With the collapse of the New Order regime and pressures for reform since 1998, NGOs are more active in serving various constituencies, though economic upset during the same period has strained their resources.

GENDER ROLES AND STATUSES

Division of Labor by Gender. Women and men share in many aspects of village agriculture, though plowing is more often done by men and harvest groups composed only of women are commonly seen. Getting the job done is primary. Gardens and orchards may be tended by either sex, though men are more common in orchards. Men predominate in hunting and fishing, which may take them away for long durations. If men seek long-term work outside the village, women may tend to all aspects of farming and gardening. Women are found in the urban workforce in stores, small industries, and markets, as well as in upscale businesses, but nearly always in fewer numbers than men. Many elementary schoolteachers are women, but teachers in secondary schools and colleges and universities are more frequently men, even though the numbers of male and female students may be similar. Men predominate at all levels of government, central and regional, though women are found in a variety of positions and there has been a woman cabinet minister.

A woman serves food at a market stand. Urban Indonesian women often find work in markets.

The vice president, Megawati Sukarnoputri, a woman, was a candidate for president, though her reputation derives mainly from her father, Sukarno, the first president. She was opposed by many Muslim leaders because of her gender, but she had the largest popular following in the national legislative election of 1999.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Though Indonesia is a Muslim nation, the status of women is generally considered to be high by outside observers, though their position and rights vary considerably in different ethnic groups, even Muslim ones. Nearly everywhere, Indonesian gender ideology emphasizes men as community leaders, decision makers, and mediators with the outside world, while women are the backbone of the home and family values.

MARRIAGE , FAMILY, AND KINSHIP

Marriage. People in Indonesia gain the status of full adults through marriage and parenthood. In Indonesia, one does not ask, "Is he (or she) married?," but "Is he (or she) married yet?," to which the correct response is, "Yes" or "Not yet." Even homosexuals are under great family pressure to marry. Certain societies in Sumatra and eastern Indonesia practice affinal alliance, in which marriages are arranged between persons in particular patrilineal clans or lineages who are related as near or distant cross-cousins. In these societies the relationship between wife-giving and wife-taking clans or lineages is vitally important to the structure of society and involves lifelong obligations for the exchange of goods and services between kin. The Batak are a prominent Sumatran example of such a people. Clan membership and marriage alliances between clans are important for the Batak whether they live in their mountain homeland or have migrated to distant cities. Their marriages perpetuate relationships between lineages or clans, though individual wishes and love between young people may be considered by their families and kinsmen, as may education, occupation, and wealth among urbanites.

In societies without lineal descent groups, love is more prominent in leading people to marry, but again education, occupation, or wealth in the city, or the capacity to work hard, be a good provider, and have access to resources in the village, are also considered. Among the Javanese or Bugis, for example, the higher the social status of a family, the more likely parents and other relatives will arrange a marriage (or veto potential relationships). In most Indonesian societies, marriage is viewed as one important means of advancing individual or family social status (or losing it).

Divorce and remarriage practices are diverse. Among Muslims they are governed by Muslim law and may be settled in Muslim courts, or as with non-Muslims, they may be settled in the government's civil court. The initiation of divorce and its settlements favors males among Muslims and also in many traditional societies. Divorce and remarriage may be handled by local elders or officials according to customary law, and terms for such settlements may vary considerably by ethnic group. In general, societies with strong descent groups, such as the Batak, eschew divorce and it is very rare. Such societies may also practice the levirate (widows marrying brothers or cousins of their deceased spouse). In societies without descent groups, such as the Javanese, divorce is much more common and can be initiated by either spouse. Remarriage is also easy. Javanese who are not members of the upper class are reported to have a high divorce rate, while divorce among upper-class and wealthy Javanese is rarer.

Polygamy is recognized among Muslims, some immigrant Chinese, and some traditional societies, but not by Christians. Such marriages are probably few in number. Marriages between members of different ethnic groups are also uncommon, though they may be increasing in urban areas and among the better educated.

Domestic Unit. The nuclear family of husband, wife, and children is the most widespread domestic unit, though elders and unmarried siblings may be added to it in various societies and at various times. This domestic unit is as common among remote peoples as among urbanites, and is also unrelated to the presence or absence of clans in a society. An exception is the traditional, rural matrilineal Minangkabau, for whom the domestic unit still comprises coresident females around a grandmother (or mothers) with married and unmarried daughters and sons in a large traditional house. Husbands come only as visitors to their wife's hearth and bedchamber in the house. Some societies, such as the Karo of Sumatra or some Dayak of Kalimantan, live in large (or long) houses with multiple hearths and bedchambers that belong to related or even unrelated nuclear family units.

Inheritance. Inheritance patterns are diverse even within single societies. Muslim inheritance favors males over females as do the customs of many traditional societies (an exception being matrilineal ones where rights over land, for example, are passed down between females). Inheritance disputes, similar to divorces, may be handled in Muslim courts, civil courts, or customary village ways. Custom generally favors males, but actual practice often gives females inheritances. In many societies, there is a distinction between property that is inherited or acquired; the former is passed on in clan or family lines, the latter goes to the children or the spouse of the deceased. Such a division may also be recognized at divorce. In many areas land is communal property of a kin or local group, while household goods, personal items, or productive equipment are familial or individual inheritable property. In some places economic trees, such as rubber, may be personally owned, while rice land is communally held. With changing economic conditions, newer ideas about property, and increasing demand for money, the rules and practices regarding inheritance are changing, which can produce conflicts that a poorly organized legal system and weakened customary leaders cannot easily manage.

Kin Groups. Many of Indonesia's ethnic groups have strong kinship groupings based upon patrilineal, matrilineal, or bilateral descent. Such peoples are primarily in Sumatra, Kalimantan, Maluku, Sulawesi, and the Eastern Lesser Sundas. Patrilineal descent is most common, though matriliny is found in a few societies, such as the Minangkabau of West Sumatra and southern Tetun of West Timor. Some societies in Kalimantan and Sulawesi, as well as the Javanese, have bilateral kinship systems.

Kinship is a primordial loyalty throughout Indonesia. Fulfilling obligations to kin can be onerous, but provides vital support in various aspects of life. Government or other organizations do not provide social security, unemployment insurance, old age care, or legal aid. Family, extended kinship, and clan do provide such help, as do patron-client relationships and alliances between peers. Correlated with these important roles of family and kin are practices of familial and ethnic patrimonialism, nepotism, patronage, and paternalism in private sectors and government service.

S OCIALIZATION

Child Rearing and Education. In the government education system, generally, quantity has prevailed over quality. Facilities remain poorly equipped and salaries remain so low that many teachers must take additional jobs to support their families.

Higher Education. The colonial government greatly limited education in Dutch and the vernaculars, and people were primarily trained for civil service and industrial and health professions. At the time of independence in 1950, the republic had few schools or university faculties. Mass education became a major government priority for the next five decades. Today many Indonesians have earned advanced degrees abroad and most have returned to serve their country. In this effort the government has received considerable support from the World Bank, United Nation agencies, foreign governments, and private foundations. Increasingly, better-educated people serve at all levels in national and regional governments, and the private sector has benefitted greatly from these educational efforts. Private Muslim and Christian elementary and secondary schools, universities and institutes, which are found in major cities and the countryside, combine secular subjects and religious education.

Higher education has suffered from a lecture-based system, poor laboratories, a shortage of adequate textbooks in Indonesian, and a poor level of English-language proficiency, which keeps many students from using such foreign textbooks as are available. Research in universities is limited and mainly serves government projects or private enterprise and allows researchers to supplement their salaries.

From the late 1970s through the l990s, private schools and universities increased in number and quality and served diverse students (including Chinese Indonesians who were not accepted at government universities). Many of these institutions' courses are taught in afternoons and evenings by faculty members from government universities who are well paid for their efforts.

The colonial government limited education to an amount needed to fill positions in the civil service and society of the time. Indonesian mass education, with a different philosophy, has had the effect of producing more graduates than there are jobs available, even in strong economic times. Unrest has occurred among masses of job applicants who seek to remain in cities but do not find positions commensurate with their view of themselves as graduates.

Students have been political activists from the 1920s to the present. The New Order regime made great efforts to expand educational opportunities while also influencing the curriculum, controlling student activities, and appointing pliant faculty members to administrative positions. New campuses of the University of Indonesia near Jakarta, and Hasanuddin University near Makassar, for example, were built far from their previous locations at the center of these cities, to curb mobilization and marching.

ETIQUETTE

When riding a Jakarta bus, struggling in post-office crowds, or getting into a football match, one may think that Indonesians have only a push-and-shove etiquette. And in a pedicab or the market, bargaining always delays action. Children may repeatedly shout "Belanda, Belanda" (white Westerner) at a European, or youths shout, "Hey, Mister." In some places a young woman walking or biking alone is subject to harassment by young males. But public behavior contrasts sharply with private etiquette. In an Indonesian home, one joins in quiet speech and enjoys humorous banter and frequent laughs. People sit properly with feet on the floor and uncrossed legs while guests, men, and elders are given the best seating and deference. Strong emotions and rapid or abrupt movements of face, arms, or body are avoided before guests. Drinks and snacks must be served, but not immediately, and when served, guests must wait to be invited to drink. Patience is rewarded, displays of greed are avoided, and one may be offered a sumptuous meal by a host who asks pardon for its inadequacy.

Whether serving tea to guests, passing money after bargaining in the marketplace, or paying a clerk for stamps at the post office, only the right hand is used to give or receive, following Muslim custom. (The left hand is reserved for toilet functions.) Guests are served with a slight bow, and elders are passed by juniors with a bow. Handshakes are appropriate between men, but with a soft touch (and between Muslims with the hand then lightly touching the heart). Until one has a truly intimate relationship with another, negative feelings such as jealousy, envy, sadness, and anger should be hidden from that person. Confrontations should be met with smiles and quiet demeanor, and direct eye contact should be avoided, especially with social superiors. Punctuality is not prized— Indonesians speak of "rubber time"—and can be considered impolite. Good guidebooks warn, however, that Indonesians may expect Westerners to be on time! In public, opposite sexes are rarely seen holding hands (except perhaps in a Jakarta mall), while male or female friends of the same sex do hold hands.

Neatness in grooming is prized, whether on a crowded hot bus or at a festival. Civil servants wear neat uniforms to work, as do schoolchildren and teachers.

The Javanese emphasize the distinction between refined ( halus ) and crude ( kasar ) behavior, and young children who have not yet learned refined behavior in speech, demeanor, attitude, and general behavior are considered "not yet Javanese." This distinction may be extended to other peoples whose culturally correct behavior is not deemed appropriate by the Javanese. The Batak, for example, may be considered crude because they generally value directness in speech and demeanor and can be argumentative in interpersonal relationships. And a Batak man's wife is deemed to be a wife to his male siblings (though not in a sexual way), which a Javanese wife might not accept. Bugis do not respect persons who smile and withdraw in the face of challenges, as the Javanese tend to do; they respect those who defend their honor even violently, especially the honor of their women. Thus conflict between the Javanese and others over issues of etiquette and behavior is possible. A Javanese wife of a Batak man may not react kindly to his visiting brother expecting to be served and to have his laundry done without thanks; a young Javanese may smile and greet politely a young Bugis girl, which can draw the ire (and perhaps knife) of her brother or cousin; a Batak civil servant may dress down his Javanese subordinate publicly (in which case both the Batak and the Javanese lose face in the eyes of the Javanese). Batak who migrate to cities in Java organize evening lessons to instruct newcomers in proper behavior with the majority Javanese and Sundanese with whom they will live and work. Potential for interethnic conflict has increased over the past decades as more people from Java are transmigrated to outer islands, and more people from the outer islands move to Java.

RELIGION

Religious Beliefs. Indonesia has the largest Muslim population of any nation, and in 1990 the population was reported to be 87 percent Muslim. There is a well-educated and influential Christian minority (about 9.6 percent of the population in 1990), with about twice as many Protestants as Catholics. The Balinese still follow a form of Hinduism. Mystical cults are well established among the Javanese elite and middle class, and members of many ethnic groups still follow traditional belief systems. Officially the government recognizes religion ( agama ) to include Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism, while other belief systems are called just that, beliefs ( kepercayaan ). Those who hold beliefs are subject to conversion; followers of religion are not. Belief in ancestral spirits, spirits of diverse sorts of places, and powerful relics are found among both peasants and educated people and among many followers of the world religions; witchcraft and sorcery also have their believers and practitioners. The colonial regime had an uneasy relationship with Islam, as has the Indonesian government. The first of the Five Principles extols God ( Tuhan ), but not Allah by name. Dissidents have wanted to make Indonesia a Muslim state, but they have not prevailed.

The Javanese are predominantly Muslim, though many are Catholic or Protestant, and many Chinese in Java and elsewhere are Christian, mainly Protestant. The Javanese are noted for a less strict adherence to Islam and a greater orientation to Javanese religion, a mixture of Islam and previous Hindu and animist beliefs. The Sundanese of West Java, by contrast, are ardently Muslim. Other noted Muslim peoples are the Acehnese of North Sumatra, the first Indonesians to become Muslim; the Minangkabau, despite their matriliny; the Banjarese of South Kalimantan; the Bugis and Makassarese of South Sulawesi; the Sumbawans of the Lesser Sunda Islands; and the people of Ternate and Tidor in Maluku.

The Dutch sought to avoid European-style conflict between Protestants and Catholics by assigning particular regions for conversion by each of them. Thus today the Batak of Sumatra, the Dayak of Kalimantan, the Toraja and Menadonese of Sulawesi, and the Ambonese of Maluku are Protestant; the peoples of Flores and the Tetun of West Timor are Catholic.

Religious Practitioners. Islam in Indonesia is of the Sunni variety, with little hierarchical leadership. Two major Muslim organizations, Nahdatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah , both founded in Java, have played an important role in education, the nationalist struggle, and politics after independence. The New Order regime allowed only one major Muslim political group, which had little power; but after the fall of President Suharto, many parties (Muslim and others) emerged, and these two organizations continued to play an important role in the elections. The leader of NU, Abdurrahman Wahid (whose grandfather founded it), campaigned successfully and became the country's president; an opponent, Amien Rais, head of Muhammadiyah, became speaker of the DPR. During this time of transition, forces of tolerance are being challenged by those who have wanted Indonesia to be a Muslim state. The outcome of that conflict is uncertain.

Muslim-Christian relations have been tense since colonial times. The Dutch government did not proselytize, but it allowed Christian missions to convert freely among non-Muslims. When Christians and Muslims were segregated on different islands or in different regions, relations were amicable. Since the 1970s, however, great movements of people—especially Muslims from Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Maluku into previously Christian areas in Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, and West Papua—has led to changes in religious demography and imbalances in economic, ethnic, and political power. The end of the New Order regime has led to an uncapping of tensions and great violence in places such as Ambon (capital of the Maluku province), other Maluku islands, and Sulawesi. A loss of authority by commanders over Muslim and Christian troops in the outer islands is playing a part. Christians generally have kept to themselves and avoided national politics. They lack mass organizations or leaders comparable to Muslim ones, but disproportionate numbers of Christians have held important civil, military, intellectual, and business positions (a result of the Christian emphasis upon modern education); Christian secondary schools and universities are prominent and have educated children of the elite (including non-Christians); and

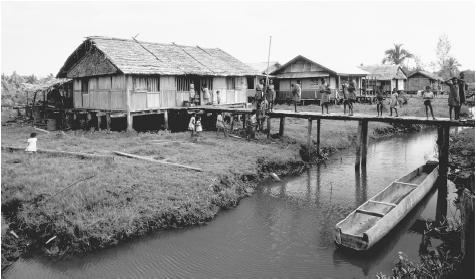

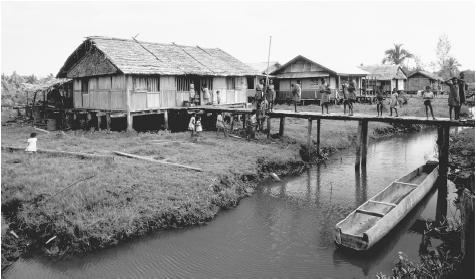

Village living is often dictated by established custom and mutual agreement by recognized leaders.

two major national newspapers,

Kompas and

Suara Pembaruan , were of Catholic and Protestant origin, respectively. Some Muslims are displeased by these facts, and Christians were historically tainted in their eyes through association with the Dutch and foreign missionaries and the fact that Chinese Indonesians are prominent Christians.

During the New Order, those not having a religion were suspected of being Communist, so there was a rush to conversion in many areas, including Java, which gained many new Christians. Followers of traditional ethnic beliefs were under pressure as well. In places such as interior Kalimantan and Sulawesi, some people and groups converted to one of the world religions, but others sought government recognition for a reorganized traditional religion through both regional and national politicking. Among the Ngaju Dayak, for instance, the traditional belief system, Kaharingan, gained official acceptance in the Hindu-Buddhist category, though it is neither. People who follow traditional beliefs and practices are often looked down upon as primitive, irrational, and backward by urban civil and military leaders who are Muslim or Christian— but these groups formed new sorts of organizations, modeled on urban secular ones, to bolster support. Such moves represent both religious and ethnic resistance to pressure from the outside, from neighboring Muslim or Christian groups, and from exploitative government and military officers or outside developers of timber and mining industries. On Java, mystical groups, such as Subud, also lobbied for official recognition and protections. Their position was stronger than that of remote peoples because they had followers in high places, including the president.

Rituals and Holy Places. Muslims and Christians follow the major holidays of their faiths, and in Makassar, for example, the same decorative lights are left up for celebrating both Idul Fitri and Christmas. National calendars list Muslim and Christian holidays as well as Hindu-Buddhist ones. In many places, people of one religion may acknowledge the holidays of another religion with visits or gifts. Mosques and churches have the same features found elsewhere in the world, but the temples of Bali are very special. While centers for spiritual communication with Hindu deities, they also control the flow of water to Bali's complex irrigation system through their ritual calendar.

Major Muslim annual rituals are Ramadan (the month of fasting), Idul Fitri (the end of fasting), and the hajj (pilgrimage). Indonesia annually provides the greatest number of pilgrims to Mecca. Smaller pilgrimages in Indonesia may also be made to

Workers harvest rice on a terraced paddy on the island of Bali.

graves of saints, those believed to have brought Islam to Indonesia, Sunan Kalijaga being the most famous.

Rituals of traditional belief systems mark life-cycle events or involve propitiation for particular occasions and are led by shamans, spirit mediums, or prayer masters (male or female). Even in Muslim and Christian areas, some people may conduct rituals at birth or death that are of a traditional nature, honor and feed spirits of places or graves of ancestors, or use practitioners for sorcery or countermagic. The debate over what is or is not allowable custom by followers of religion is frequent in Indonesia. Among the Sa'dan Toraja of Sulawesi, elaborate sacrifice of buffalos at funerals has become part of the international tourist circuit, and the conversion of local custom to tourist attractions can be seen in other parts of Indonesia, such as on Bali or Samosir Island in North Sumatra.

Death and the Afterlife. It is widely believed that the deceased may influence the living in various ways, and funerals serve to ensure the proper passage of the spirit to the afterworld, though cemeteries are still considered potentially dangerous dwellings for ghosts. In Java the dead may be honored by modest family ceremonies held on Thursday evening. Among Muslims, burial must occur within twenty-four hours and be attended by Muslim officiants; Christian burial is also led by a local church leader. The two have separate cemeteries. In Java and other areas there may be secondary rites to assure the well-being of the soul and to protect the living. Funerals, like marriages, call for a rallying of kin, neighbors, and friends, and among many ethnic groups social status may be expressed through the elaborateness or simplicity of funerals. In clan-based societies, funerals are occasions for the exchange of gifts between wife-giving and wife-taking groups. In such societies representatives of the wife-giving group are usually responsible for conducting the funeral and for leading the coffin to the grave.

Funeral customs vary. Burial is most common, except for Hindu Bali where cremation is the norm. The Sa'dan Toraja are noted for making large wooden effigies of the deceased, which are placed in niches in sheer stone cliffs to guard the tombs. In the past, the Batak made stone sarcophagi for the prominent dead. This practice stopped with Christianization, but in recent decades, prosperous urban Batak have built large stone sarcophagi in their home villages to honor the dead and reestablish a connection otherwise severed by migration.

MEDICINE AND HEALTH CARE

Modern public health care was begun by the Dutch to safeguard plantation workers. It expanded to hospitals and midwifery centers in towns and some rural health facilities. During the New Order public health and family planning became a priority for rural areas and about seven thousand community health centers and 20,500 sub-health centers were built by 1995. In Jakarta medical faculties exist in a number of provincial universities. Training is often hampered by poor facilities, and medical research is limited as teaching physicians also maintain private practices to serve urban needs and supplement meager salaries. Physicians and government health facilities are heavily concentrated in large cities, and private hospitals are also located there, some founded by Christian missions or Muslim foundations. Many village areas in Java, and especially those in the outer islands, have little primary care beyond inoculations, maternal and baby visits, and family planning, though these have had important impacts on health conditions.